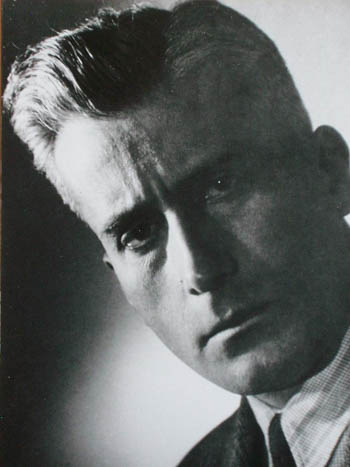

Portrait

Sándor Veress is considered to be one of the most significant Hungarian composers of the generation following Bartók and Kodály. His emulation of Bartók goes far beyond imitation. Since his life was not only marked by the wars and catastrophes of his century, but also by the solitude of an artist, who consequently went the way he felt committed to, his work is only now beginning to receive the acclaim it deserves.

The starting point of his composing technique lay in a combination of melodic phrases from Hungarian folk songs with a contrapuntal manner of composition acquired from Old Italian vocal polyphony. This led Veress to a free handling of intervals and to the combination of half or whole tones independent of tonality. As early as in his 1st String Quartet he thus made use of a composition set of twelve tones, which was, however, orientated to a tonal centre, i.e. a central tone, not a harmonic tonic. In the compositorial examination of twelve-tone music that Veress felt compelled to undertake after his emigration such a centre is always maintained. But its effect on the composition is now indirect and more differentiated. However, Veress would not go beyond the limits of the halftone; he never took quarter tones or vague pitches into consideration as structural elements.

Sándor Veress’s work is many-sided. One main emphasis lies on arrangements of songs for choirs (strongly influenced by folk music) and on demanding chamber music, either for traditional or ad hoc ensembles. Works such as his Musica concertante for twelve solo strings and Orbis tonorum for chamber ensemble transcend the limitations of chamber music. Another extremely varied group comprises his concertos for various instruments: the violin, the piano (including Hommage à Paul Klee), the oboe (Passacaglia concertante), the clarinet, for string quartet or for two trombones (Tromboniade, his last finished work). Yet another group consists of orchestral works: two symphonies, a Sonata per orchestra and Threnos in memoriam Béla Bartók. There are also large-scale works for choir and orchestra, Sancti Augustini Psalmus and Das Gasklängespiel, as well as two ballets (that both require congenial choreography). Veress finally wrote three works for one voice, Cinque Canti on poems by Attila József and the folkloristic cycle Canti Ceremissi (voice and piano), as well as Elegie on the famous text by Walther von der Vogelweide (voice and chamber orchestra). Here neither the choice of texts nor their arrangement was left to chance by the composer.

The task of making Veress’s works known to a wider public is topical. His music has a weight all of its own. Its originality and significance can be appraised either in its own right or in connection, and in comparison, to other great works of its century, be they in the tradition of Bartók to Lutoslavski and Kurtág, part of the Second Viennese School (esp. Webern) or Stravinsky, Hindemith et al.

Andreas Traub

Translation: Thomas Rüetschi